Launching SARA: A New Network for Small-Town and Rural Arts in Virginia

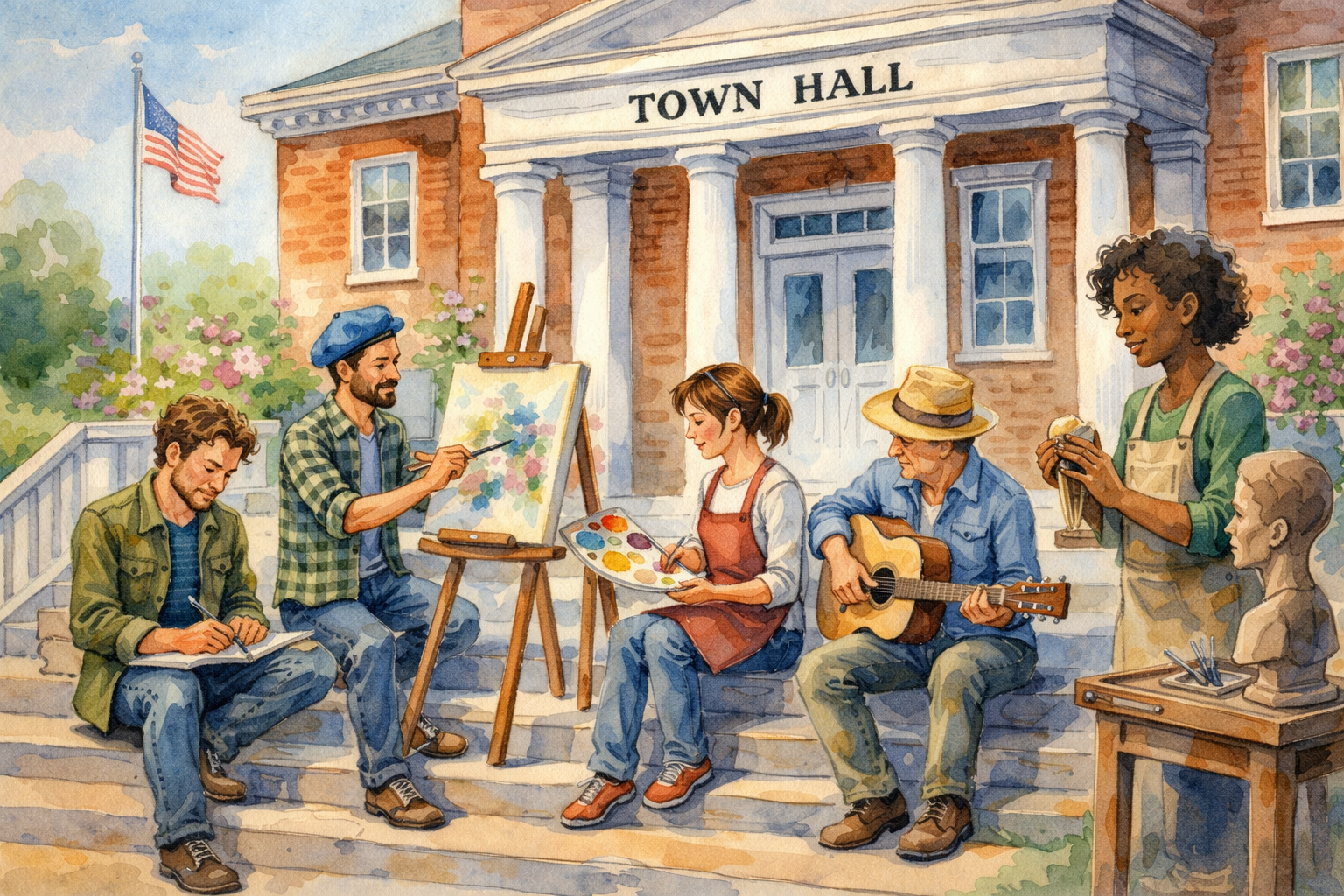

Randolph College’s MFA in Arts Leadership, in collaboration with Small Town Big Arts, launches the Small-Town Arts and Rural Arts Network (SARA) pilot in Virginia's Region 8, bringing practical strategies and sustained support to communities with limited arts infrastructure. A six-month program designed for learning through doing.

How to Use This Article:

Share this with arts leaders, community development professionals, local government officials, and grassroots organizers in rural communities who need to understand what's possible for arts activation without traditional infrastructure. Use it when recruiting workshop participants, explaining to stakeholders why arts-based strategies strengthen civic engagement, building the case for creative partnerships with existing community institutions, or demonstrating to funders how capacity-building programs can reach underserved communities that fall outside conventional arts funding models.

I'm excited to share that the Randolph College MFA in Arts Leadership program has been awarded a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts to lead a six-month pilot program that's been in the works for some time now. The Small-Town Arts and Rural Arts Network (SARA) represents an approach I've wanted to test for years: what happens when we meet rural communities where they are, with practical tools designed for their actual constraints?

This isn't about importing urban arts infrastructure models to places that don't want or need them. It's about codifying what already works in small towns and making those strategies accessible to communities that haven't had support to activate their creative potential.

Why Region 8, Why Now

We're starting in Virginia's Region 8, specifically Halifax, Mecklenburg, and Charlotte counties, because this is precisely where the need is greatest. These are counties with minimal VCA grantee presence, places where traditional arts funding hasn't reached. But here's what I've learned over two decades of working in small communities: the absence of traditional infrastructure doesn't mean an absence of creative capacity or community hunger for cultural engagement.

The pilot deliberately targets a jurisdiction with few current VCA grantees. We're testing whether we can effectively reach and support communities that have been largely outside the formal arts funding ecosystem. I also think this is an opportunity to orient the VCA to the realities and existing arts that exist in these communities.

What Makes SARA Different

The program has three core components that work together:

In-Person Workshop Circuit: We're running three half-day workshops across Region 8. The first workshop, happening March 24th at the Colonial Theater in South Hill, will be facilitated by Ash Hanson and Vivian M. Cook from the Department of Public Transformation, our national partner organization. DoPT brings deep expertise in rural creative community development; they've been doing this work at scale across the country.

Each workshop is structured around a simple premise: participants will leave with an implementable project plan. Not inspiration. Not theory. An actual plan with partners identified, timelines mapped, and next steps clear.

Regional Practice Hub: We're launching a digital resource center on SmallTownBigArts.com that will house workshop materials, practice cards, resource briefs, and action-plan templates. This isn't just a repository, it's a working space where practitioners can share progress, ask questions, and learn from each other's early wins and obstacles. I will be speaking with Meg Greene from the Rural Texas Arts and Culture Network in next week’s podcast about their online hub.

Sustained Follow-Through: Here's where most capacity, building programs fall short, they deliver workshops and disappear. We're building in 30-day check-ins, monthly virtual office hours, and two follow-up virtual workshops led by Small Town Big Arts. The goal is to help participants navigate real obstacles as they implement their plans.

Learning Through Doing

The workshop topics reflect strategies that actually work in resource-constrained environments:

Organizing without a building (pop-up programming, mobile delivery)

Partnership models with libraries, YMCAs, and community centers

Volunteer-driven governance

Micro earned-revenue approaches

Narrative change and community storytelling

These aren't theoretical frameworks. They're adapted from documented practices in successful small-town arts initiatives across the country.

The March 24th workshop in South Hill will explore arts-based organizing, partnership-building, and civic engagement. Participants will examine how creative strategies can build trust, strengthen civic participation, and expand locally-led decision-making. We'll look at concrete examples from DoPT's Engage Rural, Activate Rural, and YES! House programs—projects that demonstrate how artists and creative entrepreneurs activate third spaces and build possibility.

Building Toward Statewide Scale

This pilot is designed to generate data and insights that will inform statewide expansion. We're tracking participation by locality and previous VCA funding status. We're monitoring project commitments and follow-through. We're documenting what works, what doesn't, and why.

Virginia Tech is part of this learning process. Faculty and students from their Arts Leadership and Urban Planning programs will receive training from DoPT, preparing them to collaborate on the network's expansion. This cross-institutional approach means we're not just delivering a program, we're building regional capacity to support rural cultural development over the long term.

Why This Matters

I spent over a decade running the Academy Center of the Arts in Lynchburg that felt all the challenges of sustaining cultural infrastructure outside major metros. I've seen how thin the margin is between thriving and struggling, how vulnerable these institutions become when communities don’t understand the financial realities of combined earned and contributed income, or when boards make decisions without fully grasping the operational implications.

The SARA pilot is about preventing those crises. It's about equipping community leaders with the knowledge and tools they need to build sustainable cultural programs from the beginning. It's about demonstrating that you don't need a multimillion-dollar facility to activate meaningful arts engagement; you need the right partnerships, clear strategy, and community trust.

This is also about changing the narrative around rural arts. These aren't communities that need to be saved or fixed. They're communities with creative assets and strong social fabric. They need practical support, peer networks, and validation that their scale isn't a deficit, it's an advantage when you build systems designed for that scale.

Getting Involved

The March 24th workshop is open to community leaders, artists, and culture workers in Region 8. We're especially interested in hearing from people who are already thinking about arts-based strategies but aren't sure how to move forward—or who've tried things informally and want to understand how to make them more sustainable.

Registration is straightforward. We're asking participants to share a bit about their connection to arts and community leadership, what excites them about the workshop, and what local challenges might benefit from arts-based engagement strategies.

The Practice Hub will launch in early spring, providing resources not just for workshop participants but for any Virginia community interested in small-town arts development models.

What Success Looks Like

In six months, we'll deliver a wrap memo to VCA summarizing reach, outcomes, and recommendations for statewide expansion. But success isn't just about numbers and deliverables.

Success is changing the conversation about what's possible in rural Virginia, and building the infrastructure, not necessarily of buildings, but of knowledge and networks, to make it sustainable.

This pilot is just the beginning. But if we get it right, SARA could become a model for how state arts agencies support communities that have been chronically underserved by traditional funding mechanisms. That's worth getting right.

Part One: The Washington National Opera Departure

The Washington National Opera's departure from the Kennedy Center after 54 years offers a master class in how misunderstanding resident partnerships can destabilize an entire institution. Richard Grenell's dismissal of the opera as "not financially smart" reveals a fundamental ignorance about how performing arts venues actually achieve financial sustainability—through the patient, unglamorous work of audience cultivation that resident companies provide. This analysis examines why resident organizations matter, how they create stability in volatile industries, and what smaller arts organizations can learn from the Kennedy Center's costly mistake.

How to Use This Article:

Share this with venue directors, arts center boards, community leaders, and potential resident company partners who need to understand the economic and audience development value of these relationships. Use it when advocating for resident company partnerships, educating boards about sustainable venue models, defending existing residency agreements, or explaining to local government why hosting third-party cultural organizations creates long-term community value beyond simple rental income.

I'm continuing to examine the Kennedy Center's troubles as a way to improve nonprofit arts literacy in smaller communities. Today I want to focus specifically on resident companies and why they matter.

I ran an arts center in a city of 80,000 for over a decade. We had multiple resident companies, and they were critical to both our financial model and our relationship with audiences. In smaller communities, a single arts center or performance venue often serves as the only cultural infrastructure for a large geographical region. The ability to host local third-party cultural organizations can create long-term stability by connecting and cultivating audiences across an entire area.

The value of resident companies extends far beyond simple venue rental or programming fill. These organizations do the patient, unglamorous work of audience cultivation that host venues often have strained capacity to manage alone. A resident opera company doesn't just bring productions, it brings subscribers who attend multiple times per season, donors who feel ownership of the work, education programs that introduce new audiences to the art form, and community relationships built over years or decades. The host venue benefits from this cultivation without bearing the full cost or risk of building those relationships from scratch. When audiences develop loyalty to a resident company, they also develop familiarity and comfort with the venue itself, creating pathways for them to attend other programming. The resident company becomes an audience development engine that serves the entire facility's mission, not just its own programming slots.

When one of the Kennedy Center's long-standing resident companies departs after 54 years, we should all take note. The Kennedy Center and its current leadership continue to teach us how not to run a cultural facility, regardless of community size.

The Economics of Resident Organizations: Trading Volatility for Stability

The Washington National Opera's decision to leave the Kennedy Center represents more than an institutional divorce, it's a leadership failure that reveals fundamental misunderstandings about how performing arts venues actually work.

A Richard Grenell deleted social media post claimed that "having an exclusive Opera was just not financially smart" and that bringing in touring operas would offer flexibility. This fundamentally misunderstands how resident arts organizations function within host institutions. This isn't just wrong, it's backwards.

Resident organizations like the Washington National Opera provide predictable, stable revenue streams in an inherently volatile industry. A third-party organization focused on building and serving its own audience base takes significant financial and operational risk off the host institution's shoulders. The opera company cultivates relationships with donors, builds subscription audiences, manages production costs, and develops programming expertise, all specialized work that requires sustained institutional memory and community trust.

Touring productions, by contrast, represent speculation. You're betting that audiences will show up for companies and productions they have no relationship with, marketed by an institution that has systematically alienated much of its core constituency. Without the groundwork of cultivating a DC-based opera-going audience—the season ticket holders, the donor base, the education programs, the community relationships, you're essentially running a series of one-night stands and hoping each one succeeds.

The Washington National Opera wasn't "exclusive" in the sense Grenell implies—it was a strategic partner managing audience development and financial risk. The affiliation agreement signed in 2011 came specifically because the opera was facing financial challenges. The Kennedy Center provided infrastructure and the opera provided specialized programming expertise and its own revenue generation. This is how cultural institutions create sustainable models.

Now the Kennedy Center is assuming all that risk themselves, with a smaller staff, a politicized brand, alienated donors, and boycotting artists. They'll need to:

• Negotiate individual contracts with touring companies

• Market each production independently without the benefit of subscription sales

• Build audiences for companies with no local presence or relationship

• Compete with other venues for touring productions

• Cover costs upfront without the opera's donor base

This is "flexibility" only in the sense that being unemployed is "flexible." You have more options, but less security and fewer resources to pursue them.

The Absence of Vision: Where's the Audience Strategy?

Perhaps most damning is what we don't hear from Grenell: any coherent strategy for building audiences in an extraordinarily challenging environment.

The electoral math in Washington DC is stark. Donald Trump won 6.47% of the city's vote. While tourism provides a more diverse potential audience base, the Kennedy Center's aggressive politicization, the name change, the explicit "NO MORE DRAG SHOWS, OR OTHER ANTI-AMERICAN PROPAGANDA" messaging, the national anthem requirements, the hiring of culture war warriors, has made the institution itself a political statement.

Where's the audience development plan? How does Grenell intend to:

• Rebuild donor relationships after a well-documented collapse in contributions?

• Attract artists when high-profile names are publicly canceling commitments?

• Sell tickets when the institution's brand has become politically charged?

• Maintain tourism appeal when the building itself has become controversial?

• Cultivate local audiences in a city where 93.53% of voters rejected the president whose name now appears on the building?

These aren't rhetorical questions—they're the fundamental strategic challenges facing the institution. And we've heard nothing from Grenell suggesting he's even thinking about them, let alone has plans to address them.

Instead, we get "our patrons clearly wanted a refresh,” a claim made without evidence about patrons who are, by all accounts, fleeing the institution.

Part Two: The Washington National Opera Departure

The Washington National Opera's exit from the Kennedy Center reveals more than an institutional divorce—it exposes how projection, deflection, and the absence of strategic planning compound organizational crisis. Richard Grenell's deleted social media post dismissing the opera as "not financially smart" while claiming "our patrons clearly wanted a refresh" demonstrates leadership that wins news cycles but destroys institutions. This analysis contrasts the opera's measured, professional response with Grenell's reactive crisis management, examining what happens when ideological commitment operates without operational competence—and why the missing audience development strategy matters more than any single policy decision.

How to Use This Article:

Share this with nonprofit boards, arts administrators, community stakeholders, and governance committees who need to understand what sustainable institutional leadership looks like versus opportunistic crisis management. Use it in board training materials, leadership development programs, executive search processes, or when advocating for strategic planning and professional management practices over ideologically driven decision-making that ignores operational realities.

Let’s talk about leadership. The most revealing aspect of the Washington National Opera and Kennedy Center separation is how each organization handled it. The Washington National Opera’s statement demonstrates what actual institutional leadership looks like in crisis:

“The board and management of the company wish the center well in its own future endeavors including recognizing the center for having secured significant funding, including $275 million from Congress, for upgrades to the center.”

This is measured, diplomatic, and notably absent of blame, even when the political situation made scapegoating extraordinarily easy. The opera company could have leaned heavily into the politicization narrative, pointed fingers at Grenell’s management, or used this moment to score points with its donor base. Instead, they took the high road, preserving relationships and institutional dignity while making clear they had to leave for operational reasons.

This matters because the Washington National Opera is thinking long-term. They need to find new venue partners, maintain donor relationships, keep artists engaged, and preserve their reputation. Burning bridges, even justified ones, would undermine those goals.

Grenell’s approach represents the opposite. His now-deleted social media post claiming the opera wasn’t “financially smart” and that “our patrons clearly wanted a refresh” accomplishes several things, none of them good:

1. Deflects responsibility by suggesting this was a predetermined business decision rather than acknowledging the crisis his leadership helped create

2. Contradicts the Kennedy Center’s own statement about a “financially challenging relationship,” creating confusion about institutional position

3. Demonstrates no awareness of audience development economics or how resident organizations function

4. Abandons institutional voice for personal social media performance

5. Burns bridges with an organization the Center worked with for decades

The deletion of the post is particularly telling, it suggests even Grenell or his advisors realized this was counterproductive, but the damage was done. This is reactive crisis management, not institutional leadership.

Projection and Deflection: The Illusion of Leadership

There’s a pattern here that extends beyond arts management into broader questions of institutional governance. Grenell’s approach demonstrates what happens when projection and deflection become substitutes for strategic planning:

Project blame outward: The problem is the opera wasn’t “financially smart,” not that the political environment made their partnership untenable.

Deflect from uncomfortable realities: Talk about “flexibility” and “refresh” instead of addressing donor flight and artist boycotts.

Claim imaginary mandates: Assert that “our patrons clearly wanted a refresh” when patrons are actually leaving.

Ignore long-term sustainability: Focus on winning the day’s news cycle rather than building institutional capacity.

This might get you through a news cycle. It might even satisfy political backers who prioritize loyalty over competence. But it doesn’t sustain an arts institution that needs to sell tickets, attract donors, book artists, and serve audiences year after year.

The Washington National Opera, meanwhile, is thinking institutionally. They’re preserving relationships, managing their transition carefully, and maintaining their reputation. They’re doing the harder work of building toward long-term sustainability rather than performing leadership for an audience of one.

What This Tells Us About Governance

This case study illustrates a broader truth about institutional governance: Ideological commitment without operational competence creates the crises it claims to solve.

Grenell presumably came to the Kennedy Center believing the institution needed political correction. He implemented policies designed to reshape the organization according to his vision of American culture. These policies had predictable effects: alienating core constituencies, driving away artists, collapsing donor relationships, politicizing the brand.

Now, as consequences arrive, the response is deflection. The opera company wasn’t “financially smart.” Patrons wanted a “refresh.” These are manufactured explanations for an institutional crisis that is, in fact, a leadership crisis.

The Washington National Opera is surviving this crisis precisely because they did the opposite: they built sustainable relationships, maintained professional standards, preserved institutional dignity, and thought strategically about their long-term position. They’re not immune to external political pressures, no organization is, but their response has been measured, professional, and focused on sustainability.

The lesson for arts leaders is clear: Projection and deflection might win a news cycle, but they don’t build audiences, attract donors, or sustain institutions. Real leadership requires humility about what you don’t know, grace under pressure, honest assessment of challenges, and strategic thinking about sustainability.

The Kennedy Center is learning this lesson the expensive way. The Washington National Opera already knew it.

Follow-Up: The Kennedy Center Interview and the Irony of Manufactured Crisis

The Kennedy Center’s Richard Grenell's recent PBS interview reveals a striking irony at the heart of the Kennedy Center crisis: by misunderstanding both nonprofit finance and his own audience, the new leadership has manufactured the exact commercial failure they falsely accused previous management of creating. This analysis examines how ideologically driven decision-making, armed with partial financial literacy and absolute confidence, transformed a healthy institution into one dependent entirely on partisan fundraising—and what this cautionary tale means for cultural organizations and governance more broadly.

How to Use This Article:

Share this with local government officials, potential donors, board members, and community leaders who need to understand how cultural institutions are funded and why they matter. Use it in advocacy campaigns for arts funding, donor cultivation materials, public education efforts, or when defending your organization's financial practices and programming decisions.

In my previous post, I outlined how misinformation about nonprofit arts finance was shaping the public narrative around the Kennedy Center's transformation. I argued that the widely reported "$100 million deficit" oversimplified the institution's financial reality and exploited public unfamiliarity with how cultural nonprofits actually operate.

Now, I typically write about small town and rural arts. The Kennedy Center is far from a small town arts organization. However, I believe it's important to discuss the Kennedy Center because the drama surrounding it has become a national story. America's smaller communities are no different from other American communities in that most people don't understand the complexities of how ticket-selling cultural institutions are funded. The messaging war about the Center creates an opportunity to fill that knowledge void with falsehoods. As we watch the turmoil at our national arts center unfold, it's crucial that we actively discuss the difficult realities of cultural nonprofit management, both financial sustainability and program delivery and their relationship to each other.

In a recent PBS NewsHour interview with Richard Grenell, now president of the renamed Trump-Kennedy Center, something more troubling was reavled. There isn’t just a simple misunderstanding of nonprofit finances. What emerges is a case study in how ideologically driven leadership, armed with partial financial literacy and absolute confidence, can create the very crisis it claims to be solving.

The Educator Who Just Learned the Material

Throughout the interview, Grenell positions himself as the financially savvy adult in a room full of arts professionals who don't understand basic economics. He repeatedly patronizes the interviewer, "let me just educate you about arts institutions,” while explaining that ticket sales alone cannot sustain programming and that diversified revenue streams are essential.

He is not wrong about this. In fact, he is describing the exact model that every successful performing arts nonprofit in America already uses. What makes his tone so striking is that he appears to be discovering these principles in real time, treating century-old nonprofit financial practices as revelations of his own business acumen.

For those of us who work in this field, watching Grenell explain that arts institutions need both earned and contributed income is like watching someone explain that restaurants need both food and customers. The observation is technically correct but reveals a fundamental lack of understanding about what was actually happening at the Kennedy Center before his arrival.

The Kennedy Center has always operated on a diversified revenue model combining ticket sales, donor contributions, corporate sponsorships, federal appropriations for building maintenance, and endowment income. This is not a secret. It is disclosed in annual reports and financial statements. The institution was not failing because previous leadership didn't understand this model. They built and sustained the institution on exactly these principles for decades.

The False Diagnosis

Here is where the narrative becomes more than just condescending—it becomes destructive. Grenell came into the Kennedy Center with a diagnosis: the institution was too "woke," not commercial enough, and programming unpopular shows that couldn't sustain themselves. His solution was to rebrand aggressively, align programming with the Trump administration's political identity, and emphasize "popular" programming that would attract ticket buyers.

But look at what he now admits in the interview. When pressed about artists canceling and asked if those shows were losing money, he pivots immediately to explaining that no arts programming can be sustained on ticket sales alone. He boasts about raising $130 million while simultaneously stating that tickets provide no profit margin, that the model requires charitable subsidy regardless of programming choices.

This creates a fascinating contradiction. If commercial viability through ticket sales was never actually possible, which is what he now correctly acknowledges, then what problem was he solving? The Kennedy Center before his arrival was successfully operating on exactly the model he now describes as necessary: combining ticket revenue with substantial charitable support.

Manufacturing the Crisis

The deeper irony is that by misunderstanding his audience and market, Grenell has now created the exact financial vulnerability he falsely claimed existed before.

Washington, D.C., where the Kennedy Center is located, is a politically diverse but predominantly liberal city. The institution's traditional audience—subscribers, donors, tourists, diplomatic community, cultural professionals, reflects this demographic reality. When the Kennedy Center rebranded as the "Trump-Kennedy Center," removed Kennedy's name from prominent signage, and appointed a board chosen entirely by the president, it alienated a substantial portion of its natural audience.

The result? Ticket sales have reportedly dropped significantly. High-profile artists have canceled. The Kennedy Center Honors, once a unifying national event, saw viewership decline 35 percent despite Grenell's attempts to explain this away through broader television trends. (Notably, he could not provide actual digital viewership numbers when pressed, instead directing the interviewer to "ask CBS" while claiming "tenfold" increases he couldn't substantiate.)

So now Grenell finds himself dependent entirely on the fundraising model he once criticized, because he has damaged the commercial viability he claimed to be enhancing. The $130 million he repeatedly cites is not evidence of a new, superior approach. It is a necessary emergency measure to compensate for lost ticket revenue and to signal to remaining supporters that the institution is financially viable despite the exodus of its traditional audience.

The Republican Fundraising Machine

Grenell's fundraising success likely reflects access to Republican donor networks and corporate sponsors aligned with the administration, not a sustainable business model. This creates several problems:

First, it transforms the Kennedy Center from a national cultural institution into a partisan one. When donors give because they support the administration rather than the artistic mission, the institution becomes dependent on maintaining that political alignment. What happens in a future administration? What happens if political winds shift?

Second, it masks the underlying problem. If ticket sales provide "no profit" as Grenell states, and if the institution has alienated much of its traditional donor base, then the current fundraising is papering over a structural crisis of legitimacy and audience. The very commercial failure he accused previous leadership of creating, he has now actually manifested.

Third, it represents a category error about what sustainability means. A healthy performing arts institution has ticket revenue that provides meaningful operating margin, supplemented by contributed income that allows for mission-driven programming, capital improvements, and reserves. An institution with no profit from tickets and complete dependence on politically motivated donors is not financially healthy, it is on life support, regardless of how much money flows in during the current favorable political moment.

The Union Deflection

Grenell repeatedly mentions that the Kennedy Center has 19 unions and that this makes programming "incredibly expensive." He presents this as a novel insight and a constraint that requires dramatic change.

But the Kennedy Center has always had these unions. They were not a surprise discovered upon his arrival. Previous leadership managed these relationships while maintaining robust programming, healthy attendance, and strong community support. The existence of unions does not explain the current crisis, the current crisis explains why unions are now being invoked as scapegoats.

This pattern should be familiar: identify long-standing structural realities, present them as newly discovered problems, use them to justify radical change, then claim credit for "solving" issues that were being successfully managed all along.

Circles Within Circles

The most revealing aspect of the interview is how Grenell talks in circles. He claims previous leadership didn't understand finance, while describing the exact financial model they successfully used. He says programming must be popular and commercial, while admitting commercial revenue is insufficient. He touts fundraising success as proof the institution is healthy, while describing a dependence on charitable giving that suggests ticket sales have collapsed.

He presents himself as a clear-eyed realist cleaning up decades of mismanagement, while exhibiting the confidence of someone who has just learned the vocabulary of nonprofit finance and believes himself to be the first person to understand these concepts.

For those of us in the field, this is both darkly comic and deeply concerning. It would be one thing if Grenell simply didn't understand arts finance—many board members and donors don't, and it's our responsibility to educate them. But Grenell has enough knowledge to be dangerous. He understands individual concepts but not how they fit together, and he wields this partial understanding with absolute certainty, making it nearly impossible to have substantive dialogue about what is actually happening.

An Allegory for Governance

The Kennedy Center situation offers a microcosm of a broader pattern in governance: assume the problem is ideological, apply an ideologically driven solution, discover that complex systems are actually complex, claim credit for "fixing" things while doubling down on approaches that create new problems, then obscure the resulting failures through aggressive messaging and selective metrics.

Grenell entered believing the Kennedy Center's problem was that it was too progressive, not commercial enough, and financially irresponsible. He solved this by making it aggressively political, driving away much of its audience, and becoming entirely dependent on partisan fundraising. He now describes this situation as success, citing fundraising numbers while admitting that ticket revenue provides no profit.

The confidence never wavers. The diagnosis never gets revisited. The possibility that the original analysis was wrong, that the institution was actually healthy and his intervention caused the crisis, is never considered.

This pattern extends beyond the Kennedy Center. We see it in how complex policy problems get reduced to simple narratives, how expertise gets dismissed as bias, how manufactured crises get used to justify preordained solutions, and how the resulting damage gets reframed as success through selective measurement and aggressive messaging.

What This Means for Arts Leaders

For cultural leaders watching this unfold, several lessons emerge:

First, financial literacy is necessary but not sufficient. Grenell demonstrates that someone can understand individual concepts—ticket sales alone are insufficient, unions are expensive, diversified revenue is important, while completely misunderstanding how these pieces fit together in a healthy institution. Education must be holistic, not just focused on isolated facts.

Second, know your audience and community. The Kennedy Center's greatest asset was its position as a genuinely national institution serving a diverse cultural and political landscape. By choosing to alienate a significant portion of that audience in pursuit of ideological alignment, leadership traded long-term sustainability for short-term political advantage. The commercial failure Grenell now faces was entirely predictable to anyone who understood the D.C. market.

Third, beware of solutions that create the problems they claim to solve. When someone diagnoses your healthy institution as failing and proposes radical intervention, examine the diagnosis carefully. The Kennedy Center wasn't broken. It had challenges—every arts institution does, but it was successfully managing them. Now it faces an actual crisis of audience, mission, and legitimacy.

Fourth, transparency becomes complicated when dealing with bad faith. In my previous post, I advocated for aggressive public education about nonprofit finance. I stand by that. But the Kennedy Center case shows the limits of this approach. Grenell uses financial language to obscure rather than illuminate, citing numbers out of context and presenting normal nonprofit operations as crisis or revelation depending on what serves his narrative. When dealing with this kind of rhetorical strategy, transparency alone is insufficient—we also need critical media literacy and audiences capable of recognizing when financial information is being weaponized.

Conclusion: The Real Crisis

The tragedy of the Kennedy Center situation is not financial mismanagement, there wasn't any, despite the claims. The tragedy is that a healthy, if imperfect, cultural institution has been transformed into a politically branded entity that has alienated much of its natural audience while becoming dependent on partisan support structures that may not be sustainable beyond the current political moment.

Grenell positions himself as a truth-teller educating the financially naive about how arts institutions really work. In reality, he is someone who learned the vocabulary of nonprofit finance just well enough to misdiagnose a healthy institution, apply an ideologically driven solution that created an actual crisis, and now claims credit for solving a problem that didn't exist until he arrived.

The real lesson here is not about nonprofit finance, it's about the danger of combining partial knowledge, absolute confidence, ideological certainty, and institutional power. Whether in a performing arts center or in governance more broadly, this combination can transform functional complexity into dysfunction while the people responsible congratulate themselves on their clear-eyed realism.

For those of us committed to cultural institutions and their missions, the path forward is unchanged: we must continue to educate, to build broad-based community support, to operate with genuine transparency, and to articulate clearly what we are trying to accomplish and why it matters. But we must also recognize that sometimes the threat is not misunderstanding, it is certainty without wisdom, intervention without insight, and the confidence of those who have just enough knowledge to be dangerous.

The YES! House: The Evolution of a Creative Hub in Rural Minnesota

The YES! House in Granite Falls, Minnesota is transforming a once-vacant downtown building into a welcoming home for arts, civic life, and community connection. Led by the Department of Public Transformation, the project uses artist-driven design and strong local input to make sure the space reflects and supports the creativity that is already thriving in the town. It is a powerful example of rural revitalization through community imagination and shared cultural resources.

How to use this article: This article can serve as a valuable case study for rural arts revitalization, showing how a community can transform a neglected building into a center for creativity and civic life. It offers practical inspiration for artist-led planning and community input, helping organizations design projects that reflect local culture rather than replace it. Educators and advocates can use the story to illustrate modern placemaking strategies and support fundraising for similar efforts. It also provides a point of connection for practitioners who want to learn from and adapt the YES! House model in their own communities.

Every year I attend the Radically Rural Conference in Keene, NH. I meet some extraordinary people doing some extraordinary things. This year was no different and I was introduced to a number of organization I want to orient you to in the coming months. To begin, let’s head to Minnesota.

In the small riverside town of Granite Falls, MN, an ambitious project is unfolding: the transformation of a donated building into a vibrant community arts and civic gathering space. The YES! House stands as a strong example of how rural arts infrastructure can be designed from the ground up for collaboration and locally sourced creativity. As you may know from reading some of my other posts and listening to some of my interviews, the strongest rural arts projects utilize the creative resources and culture of a community and do not supplant them.

Origins and Site

The YES! House is located in a once vacant building and was donated in early 2018 to the nonprofit Department of Public Transformation (more about them in a future podcast and article). Rather than accepting the label of abandonment, the team took a different stance: the building was actually wanted by community members if its potential was realized. In that spirit they embraced stewardship, not ownership.

From the start, the project avoided duplicating existing assets: there was a deliberate phase of mapping community resources, learning what was already thriving, and identifying gaps rather than competing.

Design & Process

The YES! House’s programming and design were shaped by a year‐long “Artist‐Led Design Build” process. Local and national artists and architects, such as Homeboat, MO/EN Design Practice, and the Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership facilitated this collaborative effort.

During this period the team collected input from residents: about what programming they wanted, what kinds of facilities would support creativity and civic life. This approach positions the YES! House not simply as a venue but as a reflective response to rural community needs.

Purpose and Vision

At its core the YES! House is propelled by three interlocking aims:

Creative gathering space: A place for artists, community members, and civic actors to work, meet, and generate projects together.

Community asset activation: The aim is to amplify existing local arts and civic efforts, not supplant them. By acknowledging strong assets already present in the region, the YES! House seeks to build synergy rather than redundancy.

Rural renewal through creativity: The vision embraces the power of “rural creativity” to respond to community challenges and opportunities. DoPT frames this as “developing creative strategies for increased community connection, civic engagement, and equitable participation in rural places.”

Governance & Acknowledging Structural Issues

Importantly, the narrative of the YES! House includes a transparent acknowledgement of structural inequities. The organization notes that it benefits from privileges embedded in dominant nonprofit systems—white leadership, patterns of resource distribution—and commits to an ongoing journey of humility and transformation.

In fall 2022 DoPT launched the YES! House Futures Committee to guide future operations via a community‐led process.

Current Status and Invitation

While the building is still under construction, the YES! House already hosts events, tours, and regular open hours. This transitional phase underscores a key point: the house is not waiting to be “perfect” before engaging the community, it is activating now.

Why This Matters for the Arts and Rural Communities

The YES! House offers several important takeaways for the Small Town Big Arts readers:

Artist‐led design in rural contexts: It demonstrates that credible arts infrastructure in small towns can emerge through participative processes rather than top‐down models.

Complementarity vs. competition: The strategy to map existing assets and avoid duplication is especially relevant in under‐resourced communities where overlap drains scarce resources.

Stewardship mindset: The shift from “ownership” to “stewardship” aligns with newer thinking around community‐based arts ecology—where the organization acts as custodian rather than controller.

Transparency around equity and systems: By naming the privileges the organization holds and inviting shared governance, the YES! House model pushes toward more equitable rural arts infrastructure.

Activation before completion: Engaging the community before the “final build” sends a strong message about process, access, and iterative creation.

How This Could Apply More Broadly

For small‐community arts organizations the YES! House can serve as a useful case study. Some ways to adapt it:

Use a design‐build participatory process: Invite artists, residents, youth, elders to shape program from day one.

Conduct an asset inventory: Map local arts, culture, civic, physical infrastructure—identify gaps rather than reinventing.

Frame infrastructure as “stewardship” not mere “development” to emphasize community ownership.

Embed equity reflections early: Acknowledge systems of privilege and build governance structures that share power.

Activate before completion: Even with partial capacity, start hosting events, gathering feedback, adapting.

Define success broadly: Not only visits or revenue, but connectivity, resilience, community agency.

Final Thoughts

The YES! House is more than a building. It is a micro‐model of what rural arts infrastructure could become: locally grounded, creatively anchored, governance‐aware, and community‐led. For those leading the arts in small communities, it offers fresh inspiration and tangible lessons for how arts administrators can collaborate with rural places to build places and programs that resonate, endure, and evolve.

Trying to get the arts moving in your town? Consider a 501 (c)7 Social Club.

In this feature, Small Town Big Arts explores how a 501(c)(7) “arts social club”—a membership-first venue for music, dance, comedy, and cabaret—can sustain frequent programming without leaning on fragile charitable pipelines. We outline practical ticketing tactics (guest-of-member access, short-term social memberships) and a clean (c)(7)+(c)(3) hybrid that accommodates grants and education programs while keeping dues and member pricing at the core. The result is a resilient, community-owned engine for culture that aligns operations with how people actually gather.

How to Use This Article: Share with board members, venue founders, and municipal partners considering alternatives to a 501(c)(3)-only plan. Use it in feasibility studies, bylaw drafting, and budget modeling to map revenue mix and compliance thresholds. Bring it to advocacy meetings to demonstrate how member economics can sustain weekly calendars, and include it in arts administration syllabi or creative placemaking toolkits as a replicable, small-market model.

I’ve been searching for alternatives to the 501(c)(3) model for arts organizers as the nonprofit framework faces mounting strain. With the direct and largely indirect effects of declining federal support for the non-profit sector nationwide, it’s clear we need new approaches to delivering the arts in the U.S. The 501(c)(3) is especially ill-suited to sustainability in communities that lack deep private wealth, active community foundations, or strong local government backing.

While scrolling Instagram, hardly a foolproof research method, I came across the 501 (c)7 social. club Eugene V. Debs Hall via Neighborhood Evolution, and a light bulb went off. As “The Happy Urbanist,” Jon Wesolowski narrates it, “It’s about listening to the community, shaping buildings to serve people, and creating benefits that a typical business model can’t… This social hall does just that—keeping housing affordable, bringing neighbors together, and anchoring a public square.”

So, I thought, I wonder if there are any 501 (c)(7) social clubs focused on the arts? That is when I found the Ruba Club in my old stomping grounds of Philadelphia.

I found the club on a recent visit to the City of Brotherly love tucked along Green Street in Philly’s Northern Liberties neighborhood. The Ruba Club, originally the Russian United Beneficial Association, has welcomed members and artists for more than a century. Founded in 1914 and still operating at 416 Green Street, the bi-level social club marries a downstairs cabaret/speakeasy bar with an upstairs ballroom theater and full stage. Today it functions as an inclusive, nonprofit social venue with a weekly slate that ranges from cabaret and burlesque to karaoke nights and live bands, an enduring example of how a membership-forward clubhouse can double as a dependable performance engine. (rubaclub.org, The Temple News, facebook.com)

Why consider 501(c)(7) for the arts in small communities?

For small communities that want a lively, sustainable home for music, comedy, dance, or cabaret, the social-club model can be a powerful alternative (or complement) to a 501(c)(3). A 501(c)(7) exists primarily for the pleasure and recreation of members and is meant to be funded mainly by dues, fees, and member charges, not philanthropic gifts. That member-centric engine is especially well-suited to intimate venues, lounges, and halls that program frequent live performances and cultivate a “regulars” culture. (IRS) It also creates a wide sense of ownership and community engagement and is less passive than philanthropic giving.

Below is a step-by-step framework you can adapt, plus concrete ticketing tactics and a hybrid structure that combines (c)(7) and (c)(3) benefits.

1) Fit check: Is (c)(7) the right tool?

Member-first purpose. Your programming, bar/room usage, and social life should primarily serve members (and their guests). If your core aim is broad public education and grant-funded outreach, a (c)(3) may be your main vehicle. (IRS)

Revenue mix discipline. As a rule of thumb, a (c)(7) can take up to 35% of gross receipts from non-members(including investment income). Within that 35%, no more than 15% should come from the general public’s use of facilities/services. Staying under those thresholds helps preserve exemption. (IRS)

UBIT awareness. Nonmember income is generally taxable to a social club (UBTI), and too much can also threaten exemption—so design your calendar and ticketing to favor members. (IRS)

Practical signal: If you can imagine a healthy P&L driven by annual dues, member ticketing, and bar/concessions—with outsiders as the minority—(c)(7) likely fits.

2) Formation roadmap (lean, realistic, and compliant)

Incorporate a nonprofit social club in your state (articles/mission emphasizing recreation, arts, and social purposes for members).

Draft bylaws that define membership classes, admissions, dues, guest privileges, and discipline; include conflict-of-interest, fiscal controls, and dissolution clauses.

Design a membership program (see §3 below).

File for IRS recognition using Form 1024 (not 1023) with the user fee; follow Publication 557 for (c)(7) specifics. (IRS)

License & local compliance: ABC/liquor, occupancy, entertainment, sales tax, and any city permits (often easier for “member clubs,” but confirm locally).

Policies that protect status: guest rules, rentals policy, private events, comp tickets, reciprocal agreements, and a clear “members-first” event cadence.

Quick win: Prepare a one-page “Operating Intent Statement” that your board and bookkeeper use as a north star: “The club’s activities and marketing prioritize members; nonmember access is limited, controlled, and tracked for the 35%/15% tests.”

3) Membership model that actually funds the stage

A. Structure & pricing (sample):

Core Member (21+): $180/year or $20/month; benefits = members’ ticket price, priority reservations, guest privileges, member-only hours.

Household Add-On: +$90/year for a second adult at same address.

Under-30 or Artist Tier: $90/year; keep the door open to young creatives.

Supporting Member: $360/year with a few “+1” guest passes per quarter.

B. Member benefits to reinforce your exempt purpose

Member-price tickets (e.g., $10 member / $15 guest).

Members-only windows (e.g., first 48 hours of on-sale).

Members-only nights (e.g., Wednesdays + one Saturday per month).

Member lounge/balcony access, coat check, or drink specials (if permitted).

C. Guest & short-term access tactics

Guest-of-member rule (e.g., 2–4 named guests per visit).

Short-term “social membership” added to nonmember tickets (e.g., $1–$3 surcharge per ticket that enrolls buyer as a 30-day social member). This is a real-world tactic used by venues such as the Italian American Club of Las Vegas, which displays an explicit “30 Day Social Membership” charge for non-members when purchasing show tickets. (Italian American Club, CoffeeCup, Italian American Club)

Copy-ready snippet for checkout pages:

“Non-member tickets include a 30-day Social Membership surcharge, which provides temporary member access for the performance date and eligible club activities during the 30-day window.”

4) Programming & ticketing that keeps you inside the lines

A. Calendar cadence

Start with 3 member-forward nights/week (e.g., Wed/Thu/Sun) and 1 public-facing night (Fri), plus one rotating member-only Saturday each month.

Offer members-first on-sale windows and keep member allocations (e.g., reserve 60–70% of capacity for members/guests).

B. Ticket classes (example)

Member Ticket: lowest price; sold to active members only.

Guest Ticket (Member-sponsored): slightly higher; requires member ID at checkout.

Short-term Social Member Ticket: includes the 30-day add-on (auto-enrolls buyer).

Public Ticket: restricted quantity, higher price, and only for designated shows.

C. Bar & room use

Prioritize member happy hours, jam sessions, and social dances.

Rentals to outsiders should be limited and priced at market; track those revenues distinctly for compliance/UBIT analysis. (IRS)

D. Real-world analogues to learn from

Verdi Club (San Francisco) programs weekly swing nights with live bands (“Woodchopper’s Ball”)—clear example of routine live music within a social-club context. (Verdi Club, woodchoppersball.com)

Italian American Club of Las Vegas uses a non-member ticket + 30-day social membership mechanism in its showroom offerings. (Italian American Club, CoffeeCup, Italian American Club)

5) The hybrid: Pairing a 501(c)(7) club with a 501(c)(3) foundation

If your community wants both vibrant club life and tax-deductible gifts/grants for education, youth access, or heritage programming, establish a separate 501(c)(3) that can receive donations and run public-benefit programs. A clean example in the wild is the San Francisco Italian Athletic Club (a 501(c)(7)) with a separate SFIAC Foundation (501(c)(3))supporting cultural/educational efforts. (Cause IQ, app.candid.org, The SFIAC Foundation)

How to set it up responsibly:

Separate entities (articles, EINs, boards, bank accounts).

Facility-use agreement: The (c)(3) rents the room from the (c)(7) at fair market value for public programs.

Cost-sharing policy: If you share staff/gear, allocate costs with simple, auditable formulas.

Firewall the money: Donations go to the (c)(3) only; (c)(7) relies on dues/fees.

Clear branding: One “Club” (member social life) and one “Foundation” (charitable programs).

Programming split (example):

(c)(7) Club: member dances, jam nights, lounge shows, comedy lab, member holiday party.

(c)(3) Foundation: free student matinees, artist residencies in schools, heritage lectures, an annual public festival, and scholarship tickets that bring underserved residents into select events.

6) Compliance guardrails (simple, but non-negotiable)

The 35/15 guideline: Monitor nonmember receipts monthly. Keep nonmember total ≤35% of gross; within that, public facility use ≤15%. (These limits derive from legislative history and IRS guidance; they’re widely used benchmarks in examinations.) (IRS)

Track by source, not just event. Your POS/accounting should tag revenue as Member, Guest-of-Member, Short-Term Social Member, Public, Rental, Investment, etc.

Mind UBIT. Budget for tax on nonmember income; file as required. (IRS)

Marketing tone: Promote membership and members’ nights prominently; keep overt “public nightclub” messaging in check.

Governance & inurement: No private benefit to insiders; pay artists, staff, and vendors at fair market rates; document everything.

7) 90-day launch plan (template)

Days 1–30: Organization & finance

Form your nonprofit corporation; seat a founding board.

Draft bylaws and membership policy (classes, dues, guest rules).

Choose an accounting system with class/department tracking for revenue sources.

Build a dues + ticketing + bar P&L that works before nonmember sales.

Days 31–60: IRS + systems

File Form 1024 for (c)(7); gather support docs per Publication 557. (IRS)

Set up ticketing checkout to implement (a) member pricing, (b) guest tickets, and (c) short-term social membership overlay for nonmembers. (Model the 30-day add-on.) (CoffeeCup)

Adopt Facility-Use & Rentals policy (member priority; limited public/market-rate).

Days 61–90: Soft opening & calibration

Run 6–8 member-led pilots (open-mic, jazz trio, swing social, comedy night).

Add one public-facing show with limited public tickets and a 30-day social membership surcharge. Track receipts.

If you plan a hybrid, file your (c)(3) foundation in parallel and draft the MOU for space use.

8) Copy-ready templates

Membership classes (bylaws excerpt)

The Club shall have the following classes of members: (a) Core Members, (b) Household Add-On Members, (c) Under-30/Artist Members, and (d) Supporting Members. Members are admitted by application and payment of dues. Members in good standing may sponsor up to four guests per visit. The Board may authorize short-term social memberships, conferring limited privileges for a defined period not to exceed 30 days.

Guest & short-term social membership rule (policy excerpt)

Non-member attendance at performances occurs (i) as a guest of a Member, or (ii) through the purchase of a ticket that includes a short-term Social Membership (e.g., 30 days). Revenues from such sales are tracked as member-related for compliance monitoring. The Club limits public attendance and rentals to maintain nonmember receipts within IRS guidance. (IRS)

Ticketing checkout language

Non-member tickets include a 30-day Social Membership surcharge, providing member privileges for the performance and eligible activities during the 30-day period. (CoffeeCup)

(c)(7)–(c)(3) facility-use MOU (excerpt)

The Foundation (501(c)(3)) rents the Hall from the Club (501(c)(7)) at fair-market rates for public educational programs and performances. The Foundation operates its own box office for charitable events and retains program revenue. Shared costs (front-of-house, utilities) are allocated by agreed ratios and documented monthly.

9) Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

Public-heavy calendars. Solution: Flip your ratio—more member nights, advance member on-sales, and higher public prices with smaller public allocations. (IRS)

Commingled money. Solution: Separate bank accounts (and bookkeeping) for the Club and the Foundation; written cost-sharing and rental terms.

“Set and forget” compliance. Solution: Monthly dashboard showing member vs. nonmember receipts and a year-to-date 35/15 ticker.

10) Final thought

If your community craves a warm, reliable room where artists and neighbors gather weekly—swing night, songwriter circle, late-set jazz—the 501(c)(7) can be the most culturally authentic and financially realistic vehicle. Pair it with a (c)(3) for public-benefit programs, and you get the best of both worlds: a dues-driven clubhouse that keeps the lights on and a charitable arm that expands access and mission impact. Just keep the member heart beating at the center—by design, by calendar, and by the numbers. (IRS)

*Not legal advice. Before filing or selling tickets, consult nonprofit counsel/CPA and your local ABC authority to adapt these strategies to your state’s requirements.

What Powers Rural Bath County’s Cultural Ecosystem?

Nestled in the Allegheny Highlands of Virginia, Bath County is quietly leading a cultural renaissance. In this feature, Small Town Big Arts explores how two cornerstone organizations—the Garth Newel Music Center and the Bath County Arts Association—are creating deep, lasting impact in a rural community of just over 4,000 residents. Small Town Big Arts explores how even modest public investment through the a public source like the Virginia Commission for the Arts fuels creative infrastructure, civic pride, and economic vitality in one of the nation’s most arts-vibrant rural regions.

How to Use This Article: Share this with arts advocates, rural leaders, and policymakers to illustrate the value of public arts funding in small communities. Use it in grant proposals, board meetings, or advocacy campaigns to make the case for sustained investment in cultural infrastructure. Include it in arts administration coursework or community development toolkits as a model for rural arts impact.

🎧 Listen on Spotify, Listen on Apple Podcasts, Watch on YouTube

In the rolling Allegheny Highlands of Virginia, you’ll find Bath County—population 4,500—anchored by winding mountain roads, towering forests, and the kind of quiet that invites reflection. You might not expect to find a world-class chamber music center, a 60-year-old regional art show, or a new community arts hub. And yet, Bath County isn’t just home to these things—it was recently named one of the Top 30 Most Arts-Vibrant Rural Communities in America by SMU DataArts.

What sets Bath County apart? According to leaders at the Garth Newel Music Center and the Bath County Arts Association, it’s a unique blend of local vision, private generosity, and public funding that empowers rural creativity to thrive.

🎻 Rooted in Place: Music, Mountains, and Meaning

For Jeanette Fang, artistic director and pianist at Garth Newel Music Center, the answer is simple: “There’s something to be said about making music in a place of natural beauty. The harmony in nature deepens the harmony in music.”

Garth Newel has been offering concerts, residencies, and youth programming year-round since 1973. It is not just a summer festival—it is an enduring part of the county’s economic and cultural fabric. From touring across Virginia through the Virginia Commission for the Arts’ Artist Roster to hosting local K-12 string programs that fill education gaps in area schools, Garth Newel does what rural arts institutions do best: adapt, anchor, and connect.

“Without the support of the Virginia Commission for the Arts,” Fang notes, “we would lose a lot. Their touring directory helps us reach new communities. Their funding underwrites our ability to offer free or low-cost programs. They’re not just funders—they’re partners.”

🖼 A New Chapter for a Legacy Organization

Bath County Arts Association (BCAA) has been enriching the local arts scene for over six decades. Known for its flagship Bath County Art Show, which now exhibits close to 1,000 works annually, the BCAA is entering a new era. This year, the group hired its first full-time Executive Director and will soon open “The Bear”—a brick-and-mortar community arts space in downtown Hot Springs.

“I’ve received BCAA support as a student, an artist, and now as a leader,” says Sage Tanguay, the new director. “They paid for books when I was studying at UVA. Later, they helped fund dance classes I taught in the county. This organization has always believed in me—and in Bath County.”

Board President Leigh Johnson describes the Bear as a "unifying space," where residents—many of whom live miles apart across mountainous terrain—can gather for workshops, exhibitions, or just a shared conversation. It’s more than a gallery; it’s a civic living room.

📈 Statewide Arts Impact: Why Public Funding Resonates in Bath County

In 2022, nonprofit arts and culture organizations and their audiences generated a staggering $151.7 billion in economic activity across the United States. Of that, $73.3 billion came from organizational spending and $78.4 billion from event-driven audience expenditures—fueling 2.6 million jobs and contributing $29.1 billion in tax revenue nationwide.

The ripple effects are evident in Virginia. In the Richmond–Tri-Cities region, the nonprofit arts sector produced nearly $330 million in economic activity, supported 6,742 jobs, and returned over $82 million in tax revenue. Even in smaller metropolitan areas such as South Hampton Roads, arts-related economic activity reached $270 million, with audiences spending an average of $35–$36 per event beyond ticket prices.

At the heart of this ecosystem is the Virginia Commission for the Arts (VCA). Along with the Virginia Touring grants utilized by the Garth Newel Music Center, the VCA supports communities through Creative Communities Partnership grants, Community Impact grants, Arts In Practice grants, Education Impact grants, and most importantly General Operating grants. These public programs bring access, stability, and visibility to arts organizations across the Commonwealth—from urban centers to rural enclaves.

🌄 Why It Matters in Bath County

Bath County is not a metro area, nor does it generate hundreds of millions in cultural revenue. But it doesn’t need to. What Bath offers—through organizations like the Garth Newel Music Center and the Bath County Arts Association (BCAA)—is a compelling example of how small, strategic investments in the arts yield profound local returns.

With a population of just over 4,000 residents, Bath County's arts infrastructure plays an outsized role in its civic life. Public funding from the VCA is essential in sustaining this ecosystem, providing:

Stability for year-round programming, particularly during non-peak seasons,

Accessibility for underserved residents through free events, youth scholarships, and arts education,

Tourism leverage that multiplies modest grants into economic activity via overnight stays, restaurant visits, and retail engagement.

Bath County is a microcosm of what public arts funding is designed to achieve—it ensures that cultural life is not reserved for the wealthy or the urban, but is instead embedded in the fabric of every Virginia community.

🧠 Public Dollars, Big Returns

Public arts funding delivers measurable impact at every level—from national to hyperlocal. According to the AEP6 study, nonprofit arts and culture organizations generated $151.7 billion in economic activity across the U.S. in 2022, underscoring the sector’s national significance. In Virginia, the Richmond–Tri-Cities region produced nearly $330 million in arts-related activity, while South Hampton Roads contributed $270 million, both demonstrating strong returns in communities of varying sizes. At the state level, the Virginia Commission for the Arts supports a wide range of programs across the Commonwealth, including rural and underserved areas. In Bath County, while the dollar figures may be smaller, the impact is no less profound—public funding amplifies access to arts education, drives cultural tourism, and strengthens the civic infrastructure that makes creative life possible in this remote Appalachian community.

🧩 Public Funding as Cultural Infrastructure

While Bath County benefits from the generosity of local donors and seasonal residents, leaders at both Garth Newel and BCAA emphasized that private philanthropy alone cannot sustain the arts in a rural setting.

“We wouldn't exist without our membership and donors,” said Leigh Johnson, President of BCAA. “But what public funding provides is continuity and reach.”

With the recent hiring of a grant writer, BCAA is now actively pursuing state and federal funds that will deepen its community impact. Public support isn’t just additive—it’s catalytic.

“Diversity of funding is everything,” added Jeanette Fang, Artistic Director at Garth Newel. “You can’t build a resilient arts organization on private donations alone. The VCA and NEA allow us to plan—not just survive.”

That sentiment rings especially true in places like Bath County, where a single organization often serves as educator, presenter, employer, and civic hub. Without public funding, the entire ecosystem is at risk. With it, communities flourish.

🌱 Why It Matters Now

As national debates over public arts funding escalate—and as rural communities continue to grapple with underinvestment in infrastructure—Bath County offers a clear example of what happens when even modest public dollars are paired with local ingenuity.

These investments pay dividends:

Tourism driven by the arts supports local inns, restaurants, and galleries.

Youth education fills the gaps left by under-resourced school districts.

Creative placemaking encourages remote workers and former residents to return and stay.

Tangway puts it best: “In cities, if one arts organization closes, something else takes its place. In a rural place like Bath, if it’s not supplied by us, it doesn’t happen at all. That’s why we need support.”

🏛 Arts as Public Good

Virginians for the Arts, the arts advocacy organization for Virginia, is currently advocating for a $1 per capita investment in the arts through the Virginia Commission for the Arts. For a place like Bath County, that single dollar would go so very far. It would support performances in school gyms, classes in renovated storefronts, and concerts under the stars that become family traditions.

Bath County isn’t simply consuming the arts—it’s creating a model for rural cultural sustainability that the rest of the country should pay attention to.

📍 Listen to the full interviews with Bath County Arts Association and Garth Newel Music Center on the Small Town Big Arts podcast

🎧 Listen on Spotify, Listen on Apple Podcasts, Watch on YouTube

🔗 Learn more and support advocacy for public arts funding at vaforarts.org

Seeing Small Towns Anew: How “Outsiders” Can Authentically Create Art About Community

For years, small towns have been told that decline is inevitable and reinvention improbable, but in Slice of Life: The American Dream. In Former Pizza Huts, filmmakers Matthew Salleh and Rose Tucker offer a vision where empty buildings become community lifelines and abandoned chain restaurants transform into stages for hope, humor, and human connection. As Matt aptly noted, documentary filmmaking is often described as “being a fly on the wall,” but “flies on walls are very annoying”; real understanding comes from building trust, sharing meals, and truly listening.

How to Use This Article: Share this with artists interested in creating work about small communities and with arts organizers in small towns seeking to engage outside collaborators in meaningful ways. Use it in grant proposals, artist residency briefs, or board discussions on community-engaged practice.

Listen to the Podcast or Watch the Podcast

When I have approached the arts in small towns and rural places, I often focus on the art made in them — art installations in the farm land of Wisconsin, live theater in the woods of rural Virginia, murals beautifying a main street in Oklahoma. But what happens when artists from the outside turn their gaze toward these places? Can they represent small towns authentically and meaningfully?

There is a chapter in Rural Arts Management by Elise Lael Kieffer and Jerome Socolof, that discusses the difference between “outsiders” and “insiders” in the context of artists in communities. An artist can be either and be effective, but it is important they understand which one they are. This impacts how they collaborate, orient themselves to the audience, and how they produce their work. Today’s blog post looks at that orientation.

In a recent episode of Small Town Big Arts, I spoke with Australian filmmakers Matthew Salleh and Rose Tucker about their remarkable documentary Slice of Life: The American Dream. In Former Pizza Huts. The film explores a distinctly American phenomenon: abandoned Pizza Hut buildings scattered across the country, now reborn as LGBTQ+ churches, family-run restaurants, karaoke bars, dispensaries, and more.

For many, these quirky transformations might seem like curiosities. But through Salleh and Tucker’s lens, they become powerful metaphors for community reinvention and resilience — themes that resonate deeply across small-town America.

The filmmakers approached their subject with what they called an “outsider eye,” inspired by the German director Wim Wenders' approach to America in Paris, Texas. As recent transplants to the U.S., they brought curiosity and humility rather than assumptions. They didn’t rush in with a script or fixed narrative; instead, they allowed each community’s story to unfold organically.

This patient, relationship-centered approach offers a vital lesson for any artist hoping to engage with a place that isn’t their own: time and trust matter more than any artistic agenda. Before ever turning on a camera, Salleh and Tucker spent days simply being present — sitting with business owners, sharing meals, and listening.

As Matt insightfully shared, documentary filmmaking is often described as “being a fly on the wall,” but, as he put it, “flies on walls are very annoying.” Instead of invading or imposing, they aimed to blend in, to earn the trust of their subjects by showing up fully and openly.

Beyond capturing the beauty of these revitalized spaces, Slice of Life does something equally important: it doesn’t shy away from the struggles and vulnerabilities of those who create and sustain them. The film highlights the immense effort it takes to build what urban sociologists call “third spaces” — places beyond home and work where community life unfolds.

These third spaces can be karaoke bars on a quiet Tuesday night, a church that doubles as a community refuge, or a taqueria in a former pizza parlor. The film reveals the joy and pride in creating these spaces, but also the financial strain, the loneliness of leadership, and the uncertainty of waiting for people to come.

It’s a powerful reminder that community creation is both an act of optimism and an ongoing challenge. Artists and entrepreneurs alike often take on immense risks, hoping that if they “build it, they will come.” Yet, as the film shows, success rarely comes overnight, and the emotional and economic costs are real.

For artists, Slice of Life is a call to consider not just the surface of a place, but its layers of hope, struggle, and renewal. It encourages us to create art that reveals rather than dictates, that listens rather than lectures.

Tucker offered practical advice to artists stepping into unfamiliar communities: take your time, share your own story in return, and don’t arrive with rigid expectations.

Art made about small towns can be just as transformative as art made in them — if approached with care, humility, and a willingness to be changed by the process.

As artists and cultural workers, we have the privilege and responsibility to help communities see themselves with fresh eyes. In doing so, we can help them reclaim empty spaces, shift harmful narratives, and celebrate the quiet power of local dreams — in all their beauty, struggle, and resilience.

To learn more about Matt and Rose, visit their website: urtextfilms.com

What if rural revitalization isn’t about restoring the past, but designing a future?

For years, small towns have been told that decline is inevitable and reinvention improbable. But in Princeton, West Virginia, the RiffRaff Arts Collective has quietly disproved that narrative—one mural, one open mic, one coalition at a time. Their story is not just inspirational. It’s instructional. This isn’t about parachuting in solutions—it’s about planting roots, sharing power, and leading with art.

How to Use This Article: Share this with community organizers, funders, municipal leaders, and creative entrepreneurs who are tired of top-down “fixes” that ignore local potential. Use it in grant narratives, policy discussions, or case studies exploring creative placemaking. Let it be a model, a mirror, and a provocation for what’s possible when arts institutions choose coalition over isolation, and strategy over survival.

Reviving West Virginia: The Transformative Power of the RiffRaff Arts Collective. Deeply rooted in creativity, trust, and place.

I am often on the hunt for organizations and communities that can serve as models for others. I found another a great one this spring. Nestled in the heart of downtown Princeton, West Virginia, the RiffRaff Arts Collective (RRAC) stands as a beacon of creative resurgence. Founded in 2006 by the inspirational artists Lori McKinney and Robert Blankenship, RRAC has helped transform a struggling post-industrial town into a model for rural revitalization through the arts. This has been accomplished partially through grit, but also through some creative business and community impact practices.

A Vision Rooted in Community and Creativity

More than a gallery or studio, RRAC was conceived as a cultural engine for the town of Princeton, West Virginia. The RRAC is a place where artists, entrepreneurs, and community members have the opportunity to forge new futures through collaboration and imagination, something not just needed in West Virginia but in every American community. This vision has taken shape as a comprehensive, multi-dimensional effort to rebuild the civic and economic fabric of Princeton from the ground up.

The Mercer Street Renaissance

At the time of RRAC’s founding, over 80% of the buildings on Mercer Street were vacant. Through the Princeton Renaissance Project, a grassroots initiative born out of RRAC, the street has been reclaimed with more than 40 murals, community gardens, artist-run businesses, and walkable, creative infrastructure. Mercer Street now hums with vitality, offering a compelling case for the power of place-based arts investment.

Strategic Networking: Local Vision Meets Statewide Resources

A defining strength of RRAC’s success has been its outward-facing strategy. By attending statewide conferences and building relationships with arts and community development organizations, RRAC aligned its goals with broader funding streams and policy agendas. This networking not only attracted financial resources but positioned RRAC as a partner in West Virginia’s rural development ecosystem.

Anchor Events: A Pulse for the Community